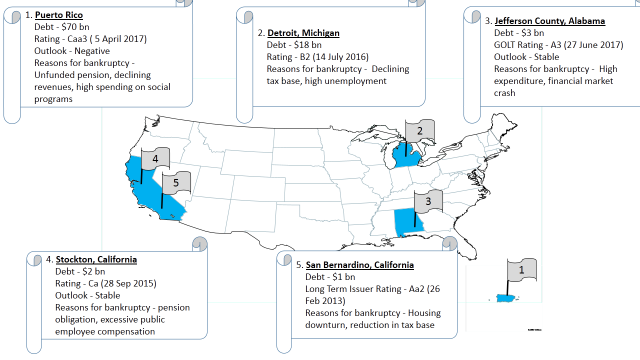

Key Learning From The US Public Finance Bankruptcy Cases

Summary

As an asset class, public finance was & is always considered to be the safe haven for conservative investors, and a good hedging instrument for active investors in the capital markets. However, some of the bankruptcies filed in the history of US public finance space defy this investment perception. This article highlights some of the key learning from the US public finance bankruptcy cases, by decoding the possible reasons behind the fall & rise of some of these US public finance entities.

Puerto Rico (2016), Detroit (2013), San Bernardino and Stockton (2012), and Jefferson County (2008), are some of the key U.S. public finance defaults in the recent past. The city of Detroit became the largest bankruptcy case in 2013 with $18 billion debt outstanding. Major reasons for most of these defaults include, housing market crisis (Stockton and San Bernardino were among the cities affected from the housing crisis in California), deteriorating economic conditions (Puerto Rico’s economy worsened when companies started shifting the base to other states on withdrawal of tax concessions), declining revenues (Detroit – high unemployment and declining tax base), high pension obligations, retirement benefits and healthcare costs (Puerto Rico had $49 bn in unfunded pension), and many more. It takes a lot of collaborated efforts and structural reorganization for a public finance entity to come out of bankruptcy. One of the landmark examples is Detroit, which swiftly exited the bankruptcy in fifteen months. The key reasons attributed are, a) it reached an early agreement with major creditors and b) successfully negotiated with all its stakeholders. There are some key learning for sovereigns/ municipals for avoiding potential bankruptcies such as identifying the early signs of troubles ahead, focusing on variety of sectors (avoiding sector concentration risk), conscious revenue and expenditure management, having sustainable pension and retirement benefits.

Let’s take a peek into some of the US sovereign or municipals defaults & key learning…

PUERTO RICO BANKRUPTCY

| Debt during bankruptcy: | US$70 bn | GDP: | $101.3 bn |

| Population: | 3.41 mn | Per Capita Income: | $19,320 |

| Unemployment rate: | 11.5% | NA | NA |

Source: Trading Economics, Bloomberg, Statista, BEA

Porto Rico filed for a historic $70 billion debt restructuring in May 2017. Puerto Rico is the largest state to default in the U.S. history with ~$70 billion in bond obligation and ~$49 billion in unfunded pensions. Puerto Rico, was barred from filing chapter 9, hence filed under Title III of the PROMESA law. Things started deteriorating for Puerto Rico when the government started to use debt proceeds to fund the budget deficit and refinance its existing debt. The situation was further aggravated by worsening economic situation.

Its economy has been reliant on the service industry for all these years due to favorable tax concessions. However, the companies shifted its base after the expiry of these tax concessions.

Drivers for filing bankruptcy:

Increasing debt combined with worsening economy led to three major credit rating agencies downgrading its general obligation bond rating to junk status (Ba2, two notches below investment grade) which triggered acceleration of debt repayments. Insufficient state revenues made it difficult to meet its debt obligation let alone meet an accelerated debt schedule.

Puerto Rico’s economy is on a declining trend primarily due to following factors:

- It has disproportionately higher spending on social programs compared to other US states despite comparatively lesser assistance from the federal government.

- It has a relatively higher poverty rate of 46.1% (2015)

- The tax revenues are constantly declining due to declining and aging population and brain drain

DETROIT, MICHIGAN BANKRUPTCY

| Debt during bankruptcy: | US$18 bn | GDP (2015): | $245.61 bn |

| Population: | 6.72 mn | Per Capita Income (2015): | $15,611 |

| Unemployment rate (11/2016): | 5.11% | NA | NA |

Source: Trading Economics, Bloomberg, Statista, BEA

Detroit filed for bankruptcy in July 2013, second biggest bankruptcy in the U.S. history after Puerto Rico. It had $18 billion debt outstanding. The city’s population dropped resulting in a drop in its property and business tax base. Increasing expenses, past unpaid bills and pension and healthcare obligations outpaced revenues by millions of dollars. Falling revenues, mainly due to decreasing tax base and high unemployment rate, and growing bills, left the city with very little to pay for even basic city services including fire and police services. Bankruptcy court approved Detroit’s plan to restructure $7 billion of $12 billion debt obligation following a two month trial. The plan outlined the total amount of debt payment to each creditor and necessary steps to be taken by Detroit to improve its city services and avoid recurrence. The city reached early deals with some of the banks. Further, it negotiated with ~30,000 employees, retirees and pensioners to take cuts in their pensions. An agreement now known as the “Grand Bargain” was made where major foundations, corporations and others would donate more than $800 million over 20 years to a fund to ease the burden on the employees and the retirees. The city-owned Detroit Institute of Art (DIA) auctioned thousands of antique pieces to help settle some creditor’s debt. The building and the art works were placed in a trust as per the deal. Part of the plan included $1.7 billion over 10 years to improve city services. Around $440 million of that to be used to reconstruct and demolish more than 40,000 vacant houses; another $430 million was allocated to improve police and fire services. A financial review committee was set up to make sure that the plan was followed. And, 15 months later in December 2014, Detroit exited the state of bankruptcy. It was a quick and efficient fix which was achieved with the help of many partners from the state, foundations, and companies like Chrysler, Ford and General Motors. It gave a blueprint to other cities struggling with huge debt. Some of the key learning from this bankruptcy case can be highlighted as:

- Reaching early agreements with major creditors

- Utilizing all the available resources (including antique, art & cultural pieces)

- Negotiating with all the stakeholders

- Help from foundations and corporates in the form of donations

SAN BERNARDINO, CALIFORNIA BANKRUPTCY

| Debt during bankruptcy: | US$1 bn | Per Capita Income: | $13,806 (2015) |

| Unemployment rate (Nov’16): | 5.3% | NA | NA |

Source: Trading Economics, Bloomberg, Statista, BEA

San Bernardino filed for bankruptcy in August 2012 when it realized that the projected expenditures would exceed the revenues by $45 million for the year. The general fund reserves had also dried up. San Bernardino is one of the victims of the massive housing downturn and recession that swept across California. The housing crisis left numerous abandoned homes and reduced the property valuations significantly. This caused reduction in property tax revenues necessary to support public service expenditures. San Bernardino depends heavily on property and sales tax revenues and the city was bound to face troubles when the revenues started depleting. In December 2016, the city won the final court approval for its restructuring plan. The plan involved cutting costs by closing its fire department and receiving services from the county and thus relieving itself of one of its largest budget items. Retiree’s healthcare costs was reduced while employee pensions were protected. Pension obligation bondholders received 40% of their claims while general unsecured creditors received only 1% of their claims. San Bernardino expects to cut $350 million in spending over 30 years as part of the restructuring plan. The city officially exited bankruptcy in June 2017.

STOCKTON, CALIFORNIA BANKRUPTCY

| Per Capita Income (2015): | $20,542 | Unemployment rate (11/2016): | 7.8% |

| NA | NA | NA | NA |

Source: Trading Economics, Bloomberg, Statista, BEA

Stockton City filed for bankruptcy in June 2012 with over $2 billion in debt and pension obligations. Stockton’s crisis was a result of years of fiscal mismanagement, housing bubble burst, excessive optimism, and excessive public employee compensation.

Housing valuations crashed by ~70% significantly crushing revenues. And interest payment schedule caused interest and debt payment to balloon up by 600%. By 2012, Stockton had already declared for fiscal emergency for two years in a row and made substantial cuts to remain solvent. But, even after the cuts, it experienced a shortfall in meeting the obligations and filed for bankruptcy. The city managed to reduce $750 million in debt and other obligations as a part of the restructuring plan. The plan called for cuts in expenses, haircuts for bondholders and an increase in sales tax approved by the city residents. However, pension remained untouched along with the benefits for current workers and the court rejected arguments of unfair discrimination among creditors. In Feb 2015, Stockton emerged from the bankruptcy.

The Union accepted Stockton’s offer to extend health insurance in retirement age past 65 to counter the demands to increase wages from city workers in 1990s. And, in 2012, it had faced over $800 million in unfunded liabilities for pension and other retirement benefits.

The economy started booming post 2000. City’s population had increased from 240,000 in 2000 to 290,000 in 2007. Its revenues were also increasing, thanks to increasing property and sales tax cash flow. The city went on a spending and hiring spree. Unions negotiated with city to increase the employee’s wage and lifetime healthcare benefits.

The city had raised $320 million through debt between 2003 and 2009 including $125 million in debt in 2007 to lower its pension costs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA BANKRUPTCY

| Debt during bankruptcy: | US$3 bn | Per Capita Income (2015): | $44,718 |

| Population: | 0.67 mn | Unemployment rate (11/2016): | 5.5% |

| NA | NA | NA | NA |

Source: Trading Economics, Bloomberg, Statista, BEA

Jefferson County filed for bankruptcy in 2011. However, the case tracks back to 1990s when the county had ordered to repair the aging sewage system by federal regulators. The project was originally estimated to cost around $1.5 billion but it eventually escalated to $3 billion, for which the county issued bonds. The plan was to pay off the debt through sewer rates charged to the customers. However, despite increasing the sewer rates it was not sufficient to repay the debt. The county entered negotiation to refinance its debt by entering into a number of interest rate swaps. The county swapped ~93% of its debt into variable rate debt, through $5.6 billion notional of swaps. Despite all initiatives by the county, it failed to pay the debt and, the county filed for bankruptcy which was then the largest in the U.S. history. Negotiations with creditors continued for two years. In June 2013, the county reached an agreement with major creditors including J.P. Morgan that, the debt would be reduced from $3 billion to $1.835 billion while sewer rates could be increased by 7.41% for four years and no more than 3.49% per year thereafter to service the debt. Jefferson County will pay around $14.7 billion over 40 years which includes $6.6 billion in debt service, $4.4 billion in operating expenses and $3.7 billion in additional annual charges.

Note:

This article is published by Girish Bhise, along with the distressed debt research team of ValueAdd. ValueAdd offers distressed debt research support for financial institutions https://www.valueadd-research.com/distressed-debt/